Over the last month, multiple sources have confirmed that PV pricing has been ticking up across the board, something last witnessed more than two years ago (Q4 2010). While spot polysilicon prices on the secondary market (mostly China) had been increasing since late December due to fears over potential antidumping duties against U.S. and South Korean manufacturers, the trend of increasing prices has now extended to primary spot polysilicon, wafers, cells and modules.

Given that structural overcapacity is still persistent, how do we make sense of this? There are a few factors at play here: first, manufacturers engaged in a serious case of inventory shedding towards the end of 2012. This had the dual effect of pushing pricing down quite significantly in Q4 2012, as well as reducing excess production in the supply chain. Second, end-demand out of China and Japan has continued its strong trend from Q4 2012, resulting in relatively strong demand in early 2013, something which has not historically been the case for seasonal reasons. And third, much of installed manufacturing capacity, while still around, has been idled over the past six months, and has not been immediately available to take advantage of the increased demand.

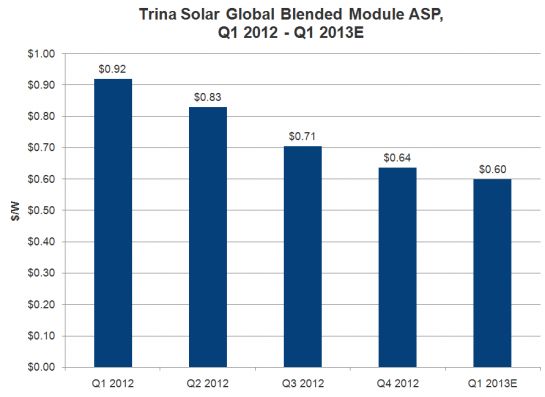

Thus far, the price increases have been small in magnitude -- around 3 percent to 5 percent -- so there is no cause for the downstream industry to be alarmed just yet. In fact, on a quarter-to-quarter basis, we still expect the trend to indicate a decline from Q4 2012 to Q1 2013 (see chart).

Source: GTM Research Competitive Intelligence Tracker, February 2013

The real question, of course, is whether this trend is ephemeral or indicative of a more sustained price increase. This is a difficult question to answer because of the looming threat of antidumping tariffs being imposed in both China (poly) and Europe (one or more of wafers, cells and modules). Had tariffs not been a factor, one would be inclined to think that pricing would soon resume its downward trajectory from Q2 2013 onward as currently idled capacity was turned back on, and installation run rates in China and Japan became less frenetic.

However, antidumping duties significantly complicate the matter. Unlike in the U.S., where the exclusion of module assembly in China in the scope of the case meant that the effect of duties was largely neutralized, tariffs in Europe could be levied on one, two or all three of wafers, cells and modules. Moreover, while Chinese producers were able to skirt the U.S. tariff in 2012 by purchasing Taiwanese cells for only an incrementally higher cost, there is hardly enough Taiwanese capacity to serve the entire European market. A strong case for meaningful increases in European pricing emerges if tariffs are levied, especially if they are levied on more than one component.

Similarly, a tariff placed on U.S. and Korean polysilicon for Chinese ingot/wafer producers would also have a meaningful impact, assuming the tariffs are declared at prohibitive (say 40 percent or higher) levels. Aside from GCL and Renesola, most Chinese poly plants are much smaller and have higher production costs than those of Wacker, Hemlock, REC and OCI. If the ingot/wafer supply chain in China switched over to domestic silicon suppliers in the wake of a tariff, it is hard to imagine that poly pricing in China would not tick upwards, which would have ramifications on pricing further down the value chain. From the perspective of Chinese component manufacturers, of course, these price increases will not result in any real margin relief.

All in all, the impending trade wars in Europe and China have set the stage for what is likely to be yet another rollercoaster ride of a year for the global PV market.

***

Shyam Mehta is a Senior Analyst at GTM Research. For more information on GTM Research Services, go to www.gtmresearch.com or contact Justin Freedman at [email protected].