The Alliance for Solar Choice, a group made up of leading solar service providers, is a staunch defender of net energy metering. And that has brought it into conflict with solar advocates calling for a more precise "value of solar" calculation.

TASC’s defense of net metering divided stakeholders in Minnesota who eventually pushed through the nation’s first legislatively mandated and PUC-approved state value-of-solar tariff. In South Carolina, TASC’s intervention could halt compromise net metering legislation crafted by a coalition of advocates and local utilities looking to create a value-of-solar formula.

TASC wants to protect net metering, which credits rooftop solar owners at the retail rate for electricity delivered to the grid. “This is a stable and highly successful policy,” TASC Executive Director Anne Smart has written. "We need to maintain net metering, not ‘fix’ it.”

Net metering is key to the third-party ownership (TPO) business model leveraged by TASC founding members SolarCity, Sungevity, Sunrun and Verengo. By effectively making use of federal tax credits, net metering and investment funds, TPO companies have driven unprecedented U.S. solar growth over the last two years.

But utilities across the country are pushing back against net metering policies, saying the practice forces them to shift costs for maintaining grid infrastructure to non-solar owners. Advocates of net metering say many of the utilities' claims are political, not based on actual cost shifts. Even in states where solar penetration is virtually nonexistent, some utilities are still attempting to change the policy.

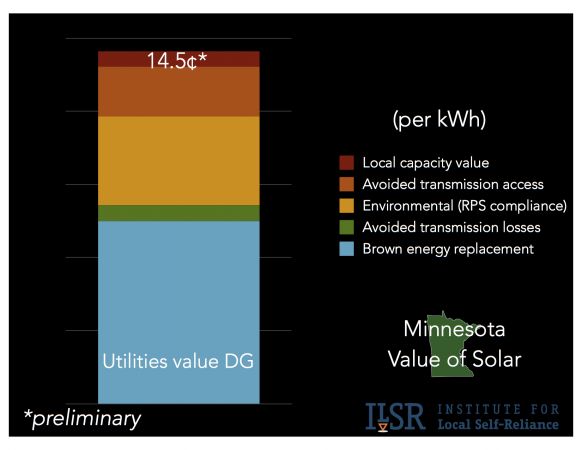

A value-of-solar tariff is a more detailed valuation of solar. As laid out in a presentation from Minnesota clean energy advocate John Farrell, a VOST credits system owners for:

- Avoiding the purchase of energy from other, polluting sources

- Avoiding the need to build additional power plant capacity to meet peak energy needs

- Providing energy for decades at a fixed price

- Reducing wear and tear on the electric grid, including power lines, substations, and power plants

Source: Institute for Local Self Reliance

Utility challenges to net metering across the country are increasingly pushing regulators into value-of-solar proceedings. Many solar advocates think the future of solar can only begin when the right VOST is agreed upon.

“If Minnesota utilities report favorably on the value of solar,” Farrell notes in the presentation, “it may change the debate in other state battlegrounds over distributed generation.”

Because it is a rigorously determined, transparent, and regulator-approved value, a VOST should eliminate utilities’ arguments about cross-subsidies, according to Karl Rabago, a former Texas regulator and utility executive who created the first U.S. VOST in Austin, Texas.

But VOST is a “buy-all, sell-all” approach in which solar owners sell “100 percent of the energy they produce back to the utility,” and then “buy 100 percent of the energy they need from the utility,” Smart wrote.

That generation sold creates “taxable revenue” for the system owner, Smart explained, and according to a legal opinion cited in a recent TASC regulatory filing, potentially makes system owners “ineligible” for the 30 percent federal Investment Tax Credit.

An effective VOST design avoids making solar owners sellers of electricity and preserves their state and federal tax benefits. That is how both the Austin and Minnesota VOSTs were designed, Rabago said.

“Legal opinions provide guidance on how to set things up,” he added. “Thanks to TASC, we have some guidance from a national law firm.”

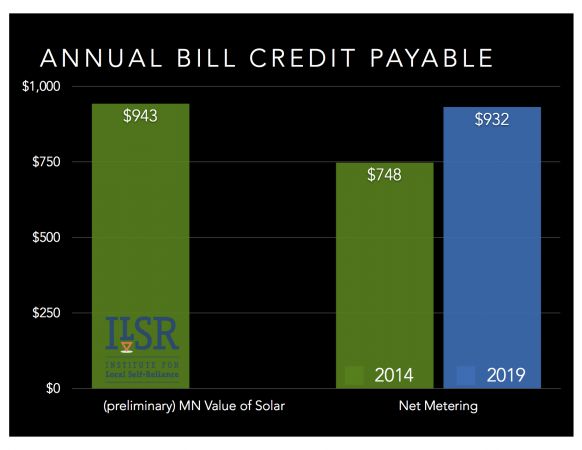

Source: Institute for Local Self Reliance

Utilities are just trying to "protect their bottom line” by setting the VOST rate, Smart wrote. After the first three years of the 25-year VOST term In Minnesota, she added, “utilities can recalculate the rate annually. [...] Solar companies will find it difficult to sustain growth and secure financing while facing yearly rate uncertainty.”

A VOST requires good-faith engagement and oversight on the part of electric utilities, Rabago said. “Utility regulators must do their job.” This means transparent ratemaking. “Well-run, open stakeholder processes, like those used in Austin and Minnesota, were vital to generating results.”

Smart predicted that Minnesota will see a three-year solar boom, followed by a bust when rates begin to fluctuate. As the retail rate rises, the VOST rate could even fall below that level, diminishing solar installation’s value proposition. “That's an unstable market that doesn't support the long-term, high-impact growth that solar is poised to achieve with net metering," she said.

“The boom-and-bust [cycle] only comes if there is no long-term commitment,” Rabago added.

A more legitimate concern is that the VOST value could be too low or too high if retail rates or technology costs change, Rabago acknowledged. “There is a [ strong ] connection between evolving rates and NEM. That’s why I included an annual adjustment in my value-of-solar” calculation.

A value-of-solar analysis “is something we desperately need,” said Rabago, who has been involved in ratemaking for 25 years. Retail rates are set by regulators using past and short-term future data. “The right price mechanism for a forward-looking technology is not backward-looking costs.”

But TASC is determined to keep net metering, a policy it says is not broken, in place to ensure consistency.

“Across the 43 states where net metering is in place, the solar industry supports thousands of jobs and hundreds of megawatt-hours of clean, distributed solar energy,” Smart wrote. “If rooftop solar is to continue its record-breaking growth, VOSTs are not the path to success.”

Solar advocates are all attempting to create a sustainable market. But with an ever-growing number of voices in the industry, there are many different opinions on how best to do it.

“There are more people today in the solar boat,” Rabago said. “Sometimes it will appear that we are not all rowing in the same direction. But we all know where we want to go.”