When Wes Kennedy started engineering solar systems in the mid-1990s, he pretty much had one integration option: batteries.

At that time, Kennedy designed and installed systems for Jade Mountain, a Colorado-based distributed energy retailer that eventually merged with Real Goods Solar. With very little policy support from utilities, the off-grid market was the dominant driver of business in the U.S. and globally. The vast majority of PV was paired with lead-acid batteries and sold to people who wanted to disconnect from the grid, or who had no other choice for electricity.

Photo Credit: Wes Kennedy

At that time, Germany and Japan also beefed up promotion laws, creating a strong burst of activity for the grid-tied market globally. In 1997, nearly two-thirds of worldwide solar deployment was off-grid. Three years later, grid-tied installations outpaced off-grid installations globally for the first time. In 2005, the market finally flipped for the U.S. as state promotion policies blossomed.

Over the last decade and a half, battery storage went from being the core enabler of solar PV to a marginal technology. Battery-based systems now only represent around 1 percent of yearly solar installations in America and throughout the world.

“Sometimes people forget that storage was the roots of the solar industry,” said Kennedy.

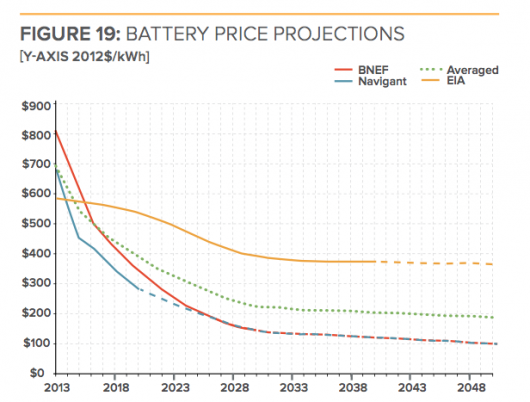

But the industry is getting back to those roots and embracing storage once again. As lithium-ion batteries get cheaper and more abundant, solar penetration reaches high enough levels to worry utilities, and electricity markets evolve to reward storage, attention has suddenly turned back to batteries.

This time, interest in the technology isn’t coming from backwoods pioneers and off-grid enthusiasts -- it’s coming from technology pioneers in Silicon Valley and savvy industry veterans who see it as the next big business opportunity.

“Storage is a big deal for our industry,” declared SunPower CEO Tom Werner during a keynote address at a recent Energy Storage Association conference.

In Germany, as feed-in tariff rates dipped below retail rates from the grid, batteries have become more popular to serve self-consumption. In the U.S., solar service providers like SolarCity and SunPower see batteries as a way to enhance their long-term relationships with customers, while also utilizing net metering and ancillary service payments to increase the value of the solar system.

“In the next five years, customers are going to decide what they pay the utility.” Tom Werner, SunPower

The applications are still very limited, but a growing number of solar companies are declaring batteries a central piece of their growth strategy.

“It’s kind of satisfying,” said Kennedy. “It’s great to see people trying to crack storage again.”

Kennedy is now developing hybrid systems at SMA, the world’s biggest inverter manufacturer. Like Kennedy, SMA also has its roots in off-grid and microgrid applications. Over the years, however, the company turned much of its attention to grid-tied applications, where most of the activity was happening. SMA put some of its hybrid inverter designs on the back burner, waiting for a time when pursuing them made sense.

“The market dictated that we mothball some of that early stuff for a big chunk of time,” said Kennedy.

The dust has finally been brushed off. SMA is boosting its investment in hybrid inverter products due to a renewed interest in microgrids, the promise of solar-storage combinations, a surge in self-consumption in Germany, and the increased use of solar to reduce diesel consumption at remote industrial and tourism sites.

Kennedy said the company’s Sunny Island inverter, which has been the core of SMA’s hybrid activities for the last decade, has been getting cheaper, more efficient and more responsive when stacked together for sites requiring up to several hundred kilowatts. SMA is also developing a central grid-forming inverter for large applications that can switch between batteries, the grid or other generating units.

Photo Credit: SMA

Currently, SolarCity is using two inverters to integrate storage at a small number of residential sites. SMA and others are betting that hybrid inverters that can handle switching demands will be the next big thing in residential and commercial solar. The question is when.

“That market is just emerging. It’s not quite there, but it’s definitely coming,” said Kennedy.

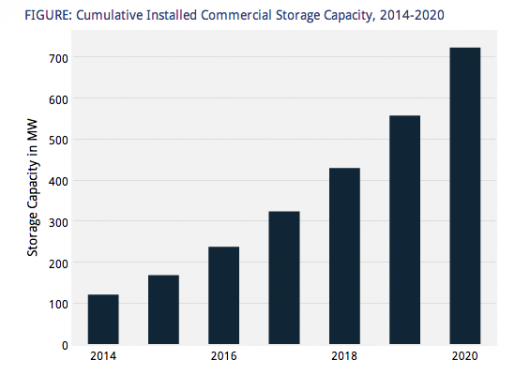

The timing of the surge is up for debate. GTM Research projects that distributed storage in the U.S. will grow to more than 700 megawatts in the next six years, partly driven by solar installers who can monetize batteries.

Some executives in the solar industry are far more bullish -- perhaps even borderline hyperbolic -- in their projections.

“In the next five years, customers are going to decide what they pay the utility,” said SunPower CEO Tom Werner in an interview. “You’ll simply be able to dial in your home lifestyle.”

Werner believes that the combination of lithium-ion batteries, home energy management software and smarter power electronics will make SunPower into an energy services provider, not just a solar supplier. And he thinks that shift will almost be complete by the end of the decade.

“Battery storage for residential, commercial, and utility-scale customers is one of the most anticipated developments in the energy space.” Peter Rive, SolarCity

SunPower has been talking publicly about storage since 2010, when it first developed its internal strategy and rolled out pilots to test solar with flow batteries, lithium-ion batteries and thermal storage. However, the company hadn’t done anything noteworthy in that arena until last month, when it announced two more residential pilots in Australia and California to outfit dozens of homes with hybrid solar-storage systems.

Last January, SunPower also partnered with Ford on a project called MyEnergi Lifestyle to demonstrate how solar, electric vehicles, smart appliances, energy monitoring and price signals could empower consumer choice. Werner said that “was one of the foundations on which we learned how to integrate storage.”

But nearly five years after declaring storage part of its business strategy, SunPower hasn’t gotten past the pilot phase. Will another five years fundamentally change the value proposition of storage for the company and its customers?

It "seems very unrealistic to assume storage will dominate solar” in five years, according to Shayle Kann, VP of GTM Research. “But if there’s any company that can move the needle on both of those technologies at once, it’s a company like SunPower.”

Others aren’t convinced it will be the solar companies that directly leverage the value of distributed storage. Jigar Shah, a partner with Clean Fleet Investors, doesn’t believe that installers and service providers are internally equipped to handle the complexities of storage regulation.

“My sense is that you’re going to have storage-only companies that really get the model right,” said Shah, speaking on GTM’s Energy Gang podcast. “I think the solar companies are going to be forced to outsource storage to those distributed storage companies.”

Listen to an Energy Gang podcast featuring a discussion about the economic impact of solar paired with storage:

America’s biggest solar installer, SolarCity, could buck that prediction, however. In April, Chief Technology Officer Peter Rive announced he was creating a grid-engineering department specifically to work on the regulatory and technical complexities of integrating storage with solar. It showed how serious the company is getting about batteries. (SunPower's Werner also said the company had hired more than 40 people dedicated to storage.)

“Any utilities or grid operators interested in exploring storage benefits such as peak shaving, frequency regulation, and voltage support should contact us,” wrote Rive in a blog post. “I’ve recently created a Grid Engineering Solutions department made up of some of the brightest minds in power systems engineering, and its mission is to help solve the challenges preventing the shift from the grid that we currently have, to the grid that we need.”

SolarCity also benefits from its close financial ties to Tesla, which is preparing to break ground on the world’s biggest factory for lithium-ion batteries. Tesla founder Elon Musk and Chief Technology Officer JB Straubel have talked extensively about using batteries for stationary applications beyond cars, and see SolarCity as a way to expand the market for storage.

“We need to be thinking bigger,” said Straubel at a recent storage event in Silicon Valley. "How do you enable super-high density of renewables on the grid? That's what drives storage over the next decade.”

The relationship between Tesla and SolarCity shows how the storage and solar industries are becoming more closely aligned.

“Storage is where solar was five or ten years ago,” said Tom Werner. “2014 for batteries feels a lot like 2003 in solar.”

Other solar veterans feel the same way. A handful of executives in the solar industry have moved into storage and are attempting to apply the financial innovation and cost-reduction lessons they learned from deploying PV.

Former SunPower President Jim Pape -- the man who helped write the company’s first plan to integrate storage with solar -- became CEO of the grid-scale flow battery company EnerVault in 2013.

Tom Leyden, who was a managing director at PowerLight/SunPower and a VP of project development at SolarCity, founded the company Solar Grid Storage in 2012; two other executives at Solar Grid Storage -- President Chris Cook and CFO Dan Dobbs -- both came from SunEdison.

The CEO of Stem, a commercial-scale distributed storage company, was the former chief executive at the CIGS thin-film company MiaSolé.

And Jigar Shah, who has invested in both Solar Grid Storage and Stem, is well known as the co-founder of SunEdison.

“We’re trying to apply the things that we learned in the solar development world to storage,” said Leyden of Solar Grid Storage.

Before the firm was acquired by SunPower, Leyden was vice president of PowerLight’s East Coast operations back in 2000, when developers “were doing projects anyway they could,” and off-grid solar was still bigger than grid-tied solar. Being a pioneer in solar-storage development is very similar, he said.

“We’re in exactly the same place right now,” said Leyden. “You figure out where to get revenues anywhere you can. That’s one of our core strengths -- we’ve been through this before.”

Solar Grid Storage works with developers to co-locate lithium-ion batteries with solar projects in the PJM region, typically in the capacity range of 150 kilowatts to 10 megawatts. Solar Grid Storage owns and operates the storage system and inverter, and makes money through providing ancillary services to the grid. The solar developer shares the Solar Grid Storage inverter, thus reducing upfront capital costs, and can use the partnership to offer customers backup power or help them reduce demand charges.

Solar Grid Storage has four projects in the ground and another five in contract negotiations. Each project is still difficult to execute, said Leyden, but he sees it getting easier as market rules improve around the country and investors get more comfortable with the concept.

“This is going to accelerate faster than solar,” he said. “In the next five years, I can’t imagine a solar system [being] installed without storage.”

Despite the excitement and predictions about widespread use of storage in the solar industry, companies are barely scratching the surface. Installations in the U.S. number in the dozens. And although lithium-ion battery costs have dropped 40 percent since 2010, adoption is still limited to wealthy customers willing to pay a premium or to commercial customers in markets where storage can cut demand charges.

Photo Credit: Rocky Mountain Institute

“Millions of customers, commercial earlier than residential, representing billions of dollars in utility revenues will find themselves in a position to cost-effectively defect from the grid if they so choose,” wrote the authors.

As SolarCity’s Peter Rive spelled out in a blog post in April, his company “has no interest in this scenario.” Solar companies understand the value of the grid, and are not looking to entirely displace customers. But the potential to defect will realistically be there for a growing number of people -- putting more than $30 billion at risk for utilities.

“In conversations with utilities, they’re terrified,” said SMA’s Kennedy. “It’s certainly not mainstream, but the solar-storage option seems to be coming.”

Utilities may be nervous, but storage providers are thrilled at the prospect of leading solar companies embracing solar.

Photo Credit: GTM Research

In his keynote address at a storage conference earlier this month, SunPower’s Werner said that solar advocates “need to accept” the reality about the need for more distributed and centralized storage. He described SunPower’s intention to work closely with storage companies to create more demand for the technology.

“We’re interested in partnering, using your technology or investing in it,” proclaimed Werner.

After finishing his speech, an audience member stepped up to the microphone and expressed his gratitude for Werner’s comments. “Everyone in the room should be standing up and doing a happy dance about a solar executive saying what you said,” explained the man. “Only a few years ago, a solar executive would never have said that.”

The rhetorical shift among solar executives like Werner has certainly been notable. But the actual business shift has yet to fully materialize. For now, with limited applications, solar companies are attempting to find the local value of storage and figure out how it can fit into existing installation and service models. That’s a challenge reminiscent of the early days of solar.

But it’s nothing that hasn’t been done before.

“The horse is out of the barn. It will happen,” said Werner. “Just like solar, you’re going to get scale and you’ll get costs down. We as a company are banking on it.”

For an in-depth look at how storage, solar and home energy management may start to change electricity delivery, come to GTM's Grid Edge Live conference in San Diego on June 24-25.