Almost exactly three years before Sandy, on October 27, 2009, President Obama stood in front of a 25-megawatt solar farm in southern Florida to deliver his vision for a 21st-century grid. The speech was one of many on a cross-country tour to highlight the newly passed stimulus package, which set aside $90 billion to support renewable energy projects and smart grid technologies.

Joined by Lew Hay, CEO of the Florida utility FPL, President Obama was in Arcadia, Fla. to announce a $3.4 billion package of investments for smart grid projects -- mostly advanced meter deployments -- to build a “smarter, stronger, and more secure electric grid.”

Photo Credit: White House. Obama announces the stimulus smart grid package in 2009.

For 15 minutes, the president spoke about the economic and efficiency benefits of the smart grid, occasionally mentioning the need to reduce power outages. The word “resilient” never came up.

Fast forward to October 2012. Working off a $200 million grant through the stimulus package, Maryland utility Baltimore Gas & Electric (BGE) had just deployed 100,000 smart meters, reaching 10 percent of its goal to digitally connect 1 million gas and electric meters. Like the president, BGE officials weren’t thinking much about resiliency. The meters were mostly for improving energy efficiency and demand response, not outage management. And then Sandy swept through Maryland, knocking out the power for nearly 200,000 of its customers.

Even though the meters were not fully integrated into the utility’s centralized outage system, BGE had a new way to monitor where the power was out in its territory. By sending messages to the meters to see if they responded, the utility was able to locate where to send crews in the field or verify if power had been turned back on. It was a huge leap from BGE’s previous callback system, which required staff to make phone calls to customers in order to determine whether the electricity was back on.

Within 48 hours, 90 percent of BGE’s customers had their power restored. The utility calculated it had saved more than $1 million in labor costs by more efficiently deploying line workers and eliminating the need for 6,000 truck deployments.

“That was really when we saw an opportunity to later leverage the project,” said Chris Burton, vice president of BGE’s smart grid business. “Resiliency and reliability were not the biggest tickets at the time the project was first announced, but we saw their value.” The utility now has 650,000 smart meters installed.

Neighboring utility Pepco, which operates in Maryland and Washington, D.C., saw the exact same benefits. Sandy caused more than 100,000 outages in Pepco’s territory. By leveraging its newly built smart meter infrastructure, the utility was able to restore power for 95 percent of customers within 48 hours. That was a major improvement over its performance during the June derecho, which took the utility by surprise and left hundreds of thousands of customers without power in the sweltering heat for nearly a week. In the days before Sandy, Pepco’s president assured the public that thousands of new smart meters would help the utility better prepare for the storm. And they did.

“What we’ve learned from Hurricane Sandy and other disasters is that we’ve got to build smarter, more resilient infrastructure that can protect our homes and businesses, and withstand more powerful storms.” President Obama

There was one glaring problem, however. In nearly every other Northeastern state struck hardest by Sandy -- Connecticut, New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts -- there were virtually no networks of smart meters deployed. Utilities had developed plans over the years, but regulators worried about cost and security had delayed the projects. That left big gaps in how utilities alerted customers and managed repair jobs during the storm. It’s an issue faced by many power companies across the country that still depend on manual processes to verify and fix outages.

PSE&G had many situations in New Jersey where it could have saved manual visits or phone calls to verify power restoration if it had had smarter meters in place. Without the technology, the utility couldn’t tell if individual houses were receiving electricity after repairing circuits. “That’s an infrastructure gap that, candidly, is a policy debate where the regulators say they don’t want to spend the money,” said Izzo.

The lack of intelligence in its technology frustrated Izzo. So while New Jersey regulators delayed large-scale smart meter rollouts, PSE&G focused further out on its distribution system and proposed one of the most comprehensive deployments of intelligent technologies on the grid.

As part of Energy Strong, PSE&G’s $1 billion post-Sandy hardening plan, the utility plans to spend $100 million on fault location, isolation and service restoration (FLISR) -- an application gaining traction in the U.S. that can help better detect faults and isolate problems on distribution circuits. That investment in FLISR rivals what any other utility has made thus far.

The utility will also spend another $100 million on remote controls for substations and a distribution management system (DMS) that can pull together maps, outage reports, information from field crews, SCADA data, customer information and data from equipment in the field into one system. Even after getting whittled down by regulators from its original $3.9 billion spending target, it will be one of the biggest rounds of spending on distribution grid intelligence since Sandy.

Photo Credit: BGE. Smart meters saved 6,000 truck rolls like this one for BGE.

With $200 million in assistance from the stimulus package, Con Edison is also investing quite heavily in distribution management capabilities that will give it a better view of its grid network in New York City. When completed, it will network SCADA systems, FLISR and smart meters into one system -- potentially helping link together buildings with intelligent control systems and electric vehicles. The ambitious project was initially announced in 2009 on the same day the president was visiting Florida touting his smart grid plan. However, it was not in place during Sandy -- and parts of the system still have not been finished.

When Con Edison’s $1 billion grid hardening plan is completed and its distribution management system fully integrated, executives are confident that company will be very different than it was before Sandy. “When all is said and done, a Sandy-like event will have a much smaller impact on the system,” said Con Edison’s John Miksad.

***

In June 2013, President Obama stood in front of hundreds of students at Georgetown University. Instead of talking about green jobs and new investments in the clean energy economy -- topics that had faded somewhat from his speeches at that point -- the president was there to talk about climate change.

When the topic of infrastructure came up, Obama struck a different tone than in past speeches: “What we’ve learned from Hurricane Sandy and other disasters is that we’ve got to build smarter, more resilient infrastructure that can protect our homes and businesses, and withstand more powerful storms.”

Manmade climate change, he said, had “contributed to the destruction that left large parts of our mightiest city dark and under water.”

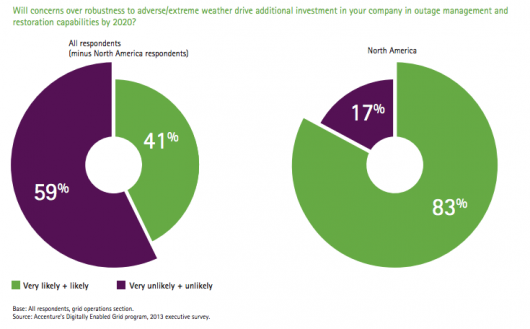

Photo Credit: Accenture. North American utilities report resiliency as a top technology driver.

The speech was a pivotal moment for the White House, which was trying to show it was serious about addressing the climate. It was also part of a broader shift in the power sector, where utilities were starting to think differently about infrastructure development. In 2009, the buzzword within the industry -- and thus the political realm -- was “smart grid.” After Sandy, it was largely about “resiliency.”

A 2013 survey from the consulting services company Accenture backed that up. When U.S. utilities were asked their top reason for integrating IT on the grid to make it smarter, 97 percent identified reliability and outage management as top concerns. In Europe, where grid reliability historically has been much higher than in the U.S., every single utility surveyed said the top priority was distributed energy integration.

When American power companies were asked if recent extreme weather events had driven smart grid investments, 83 percent responded in the affirmative. “It is a top priority. Utilities believe they've got a lot of work to do in that space, and they are now planning to invest,” said Jack Azagury, the global managing director of Accenture’s smart grid services unit.

It hasn’t been a top priority in recent decades. Throughout the 1990s, satisfied with reliability improvements, U.S. utilities significantly reduced spending on distribution infrastructure from 5.7 percent of revenues in the 1980s to 3.5 percent in the 1990s. The result: a $57 billion gap in spending that the American Society of Civil Engineers has said needs to be filled by the end of the decade to replace outdated, aging equipment.

The stimulus package provided a needed surge. As of March 2014, the $4.5 billion spent by the government on grid modernization resulted in more than $5 billion in private investment to install 14 million smart meters, nearly 350 advanced grid sensors, the digitization of 6,500 distribution circuits and development of more than a dozen storage projects. But even the Department of Energy, which oversaw the stimulus grid program, admitted those projects were “a relatively small down payment” on the hundreds of billions of dollars needed to bring the distribution and transmission system up to modern standards.

“I don't think that utilities have been doing a poor job. I think they've been doing as well as they typically could, given restrictions around the technology they were using.” Rick Nicholson, Ventyx

Anecdotally, utilities have reported numerous benefits from the stimulus: thousands of fewer truck rolls; millions in operational savings; and hours in saved outages. But with limited nationwide data after 2011, it has been difficult to determine how far those benefits have spread since Sandy.

The most recent data from Ventyx showed a lack of progress in the industry as of 2011. When the Associated Press looked at information provided by the software company, it found that the average power outage was 15 percent longer in 2011 than it was in 2002. Throughout that same decade, spending per customer on distribution equipment and maintenance -- not including power plants or transmission lines -- rose by one-third; however, the number of nationwide outages stayed virtually the same. Those statistics didn’t take into consideration any of the big extreme weather events like Hurricane Irene or the October snowstorm in 2011.

“I don't think that utilities have been doing a poor job. I think they've been doing as well as they typically could, given restrictions around the technology they were using,” said Rick Nicholson, head of Ventyx’s transmission and distribution business, which was bought by the large power automation company ABB in 2010.

Listen to a recent Energy Gang podcast with Ventyx's Rick Nicholson, where we discuss how much progress utilities have made since Superstorm Sandy:

Conversely, Ventyx and the Associated Press found one mildly positive statistic that mentioned previously: power restoration after Sandy was faster on average than any other hurricane since 2004, even though it caused the largest number of outages in U.S. history. Although many utilities are still feeling the impact of the long period of lagging investment, Nicholson said that power providers are slowly starting to change. The post-Sandy recovery was a sign that smarter OT and IT is making its way onto the grid.

“Clearly, the availability of more advanced technology like smart meters and distribution SCADA systems are having an impact. It’s also because utilities are putting more emphasis on [technology] as the number of storms increases,” said Nicholson.

***

With stimulus funds dried up, resiliency has become a more important driver of grid modernization, even for utilities outside of Sandy’s path. This has a direct impact on how technologies are integrated as companies try to build on the technological foundation laid by recent government investments.

There are five major technology areas that can provide utilities a better sense of what’s happening on the grid, and some of them have been given a boost by the stimulus. The first are smart meters and the communications systems that link the meters, known as automated metering infrastructure. The second are the geographic information systems and SCADA that can analyze locational data and provide remote control capabilities. The third are the outage management systems (OMS) and distribution management systems (DMS) to track issues on the grid. The fourth are the mobile workforce management systems, which all utilities use to track jobs out in the field. And the fifth are business analytics tools that help utilities make sense of the large amounts of information across the grid.

“We’re starting to see a much greater emphasis on integrating these systems,” said Nicholson.

Photo Credit: FirstEnergy Corp: Utility systems for addressing outages are starting to converge.

Utilities are making an effort to bring these disparate elements together in ways that improve operations and the customer experience. After Sandy, for example, JCP&L invested tens of millions of dollars in new mobile capabilities for its outage management system to help deliver information to lineworkers in the field, track mutual assistance crews and give customers an up-to-date view on outages. That system was developed as a direct response to criticism that the utility wasn’t keeping customers adequately informed.

“That information is readily available, not just during storms, but during blue-sky days as well,” said JCP&L’s Tony Hurley. “We are much better off with these changes.”

Scott Olson, who was deputy mayor of Byram Township, New Jersey during Hurricanes Irene and Sandy, witnessed those integration problems within JCP&L. From late 2011 through 2012, his town experienced an aggregate total of more than 30 days of outages -- and he was getting frustrated.

On daily conference calls with company executives to get updates, Olson heard conflicting reports about when power would be restored. “They just didn’t have the information,” he said. When talking to crews on the street, Olson saw that they had paper maps of the grid that didn’t show streets. The line workers would go up to the pole, look at the number imprinted on it, and compare it to the map -- while simultaneously using a compass to figure out which direction they were facing. And when JCP&L set up an online map to track outages, the display was consistently incorrect.

“They were clearly trying to do their best, but they were trying to get information for us and they just couldn’t find it,” said Olson. “The situation seemed pretty ridiculous in modern America.”

While its new outage system is an important step for JCP&L, that level of communications integration is still a baby step compared to the type of integration that is possible. The sixth -- and most nascent -- technology area is the advanced distribution management system (ADMS). It’s the holy grail of resiliency, which is why a lot of the big grid automation companies are chasing it.

To understand the potential of ADMS, it’s helpful to understand how the other response systems at a utility work.

Photo Credit: PSEG. A utility employee manages a job through the mobile workforce system.

Outage management systems have been the core of utility control centers since the 1980s, when direct digital controls became common. Those systems relied mostly on analyzing patterns of phone calls and comparing them to outages in the field. They were much better than the completely manual systems used before, but early outage management capabilities were unable to reliably provide situational awareness. Newer systems have integrated digital mapping tools. As illustrated in the case of BGE and Pepco during Sandy, smart meters and other sensors have also enhanced monitoring capabilities.

Utilities also use a mobile workforce system to dispatch crews and update work orders. Traditionally, outage systems and workforce systems were separate. But over the years, they have been merged, usually through custom integration. Newer platforms now offer the two in the same package and have expanded beyond laptop computers to handheld devices -- sometimes benefiting mutual assistance crews visiting from other utilities. That’s what JCP&L has done.

Finally, the traditional DMS brings together SCADA systems, mapping and demand modeling tools together on one platform. Sometimes, the outage and workforce platforms are fully integrated with the DMS, but it often runs separately.

An ADMS combines all of these systems together, while also bringing in all the new information from meters and sensors that have recently been deployed in the field. In theory, a utility engineer or CEO could have access to any combination of data in one place: damaged circuits, location of crews, status of jobs, maps of the service territory, damage estimates, and even social media feeds from customers locating outages. And outside of a crisis situation, the utility would be able to monitor voltage levels, demand on the grid, and performance of distributed systems like solar and batteries.

At a time when consumers expect everything to be connected, it may seem surprising that these capabilities are only now coming together. Part of the issue has been the availability of technology: many of the enabling devices in the field were only deployed as a result of funding from the stimulus package. Part of the issue has also been culture; operations and IT teams within utilities have historically operated in silos. And there’s also cost; spending tens or hundreds of millions of dollars on new equipment and the overlaying software can be a tough sell to some regulators.

“It’s all about a question of priorities and budgets. Even when a technology is there and the business case is strong, utilities may not go for it,” said John McDonald, director of technical strategy at GE Digital Energy.

That’s not stopping companies from trying. In the last few years, major grid software and hardware providers -- Alstom, GE, Oracle, Schneider Electric, Siemens and Ventyx/ABB -- have beefed up their ADMS offerings and used recent extreme weather events as a way to pitch utilities on the benefits. Utility adoption is increasing around the country, but traditionally conservative power companies are still somewhat slow to integrate such advanced systems.

“There’s a lot of attention around reliability, but I think the next big wave of investment is going to be around distributed energy resources and how they're being incorporated into the grid” Gary Rackliffe, ABB

However, if there’s anything that could accelerate ADMS adoption, it might be another potential “threat” to the way utilities have historically managed infrastructure: distributed generation.

Accenture’s 2013 industry survey found that utilities in America were far more interested in using information technology for outage management, while utilities in Europe were mostly interested in using it for integrating distributed energy. But as the U.S. starts to catch up with Europe in renewable energy -- and states like California, Hawaii and New Jersey put enough distributed resources like solar on-line to start challenging circuits and cutting demand -- an integrated approach to grid management may appeal to more utilities.

“I think that's how the U.S. market is moving forward. There’s a lot of attention around reliability, but I think the next big wave of investment is going to be around distributed energy resources and how they're being incorporated into the grid,” said Gary Rackliffe, the vice president of smart grid development for ABB. “We’re seeing a lot more attention in this area.”